Meet Dr. Nadine Caron

General Surgeon

Dr. Nadine Caron is a general surgeon, researcher, and professor at the University of British Columbia. A mother and outdoor-enthusiast, Dr. Caron is also the first female First Nations general surgeon in Canada. Her current work centers around advocating for Indigenous populations and addressing inequity in healthcare.

STEM to the Sky

Apr 26, 2022

- How were you introduced to STEM and what made you pursue medicine?

- Is there anything that surprised you along your journey?

- What is the most rewarding aspect of your work?

- How would you compare teaching versus practicing medicine?

- Can you walk us through a typical day in the life?

- How do you find balance in your life?

- Can you tell us more about your TEDx talk,

- What do you hope younger students understand about their futures?

- What advice do you have for a student who is interested in pursuing medicine?

- What do you hope to see in the future of healthcare?

How were you introduced to STEM and what made you pursue medicine?

At Westside Secondary High School in Kamloops, where I grew up, I had some great teachers in the sciences. They showed that science could be interesting, fun, and something that you could work to understand. It had all of those “aha” moments when I would struggle over a concept and then something would finally make sense. It was one of those areas where I found that you didn’t have to memorize things if you took the time to understand them, and then you could apply the topics to a bunch of different areas.

When I left high school, I played basketball at Simon Fraser University and studied kinesiology, the study of the human body and how it works. Physiology, anatomy, and pathophysiology were all fascinating to me. I was able to apply much of what I had learned in the STEM subjects that I studied in high school but in a context that I could really understand as an athlete. It was great to understand when and how things happen on a basketball court or in other sports—you can really boil it down to the understanding of the science behind it all.

It was that mixture of science and the human body that really set things up nicely for me to go into medicine. It was the perfect career for me to not only understand it, but then to use that understanding and passion to help other people as you tried to figure out what is wrong and what you can do to be part of the solution to fix those symptoms for that condition.

Dr. Nadine Caron in 2010 (Credit: Simon Fraser University)

Is there anything that surprised you along your journey?

Every time I went into something, whether it was kinesiology at Simon Fraser University, medicine at the University of British Columbia, public health at Harvard, or surgical endocrinology at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), what amazed me is that I thought I knew what I was signing up to study. But, it really just opened more doors. If opportunities are this big mansion, you walk down a hallway, you pick a door, you walk through it, and you’re going to study that room. I realized that it actually just opened more opportunities and more choices.

When I signed up to be a general surgeon, I became a general and endocrine surgeon. Then, I started doing research and started expanding my career in public health. I started the Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Health with some amazing colleagues at UBC. I started to understand the context of our healthcare system for rural, northern, and indigenous Canadians. The more you go into things with your eyes wide open, the more you’re going to get out of it and more opportunities are going to come to you.

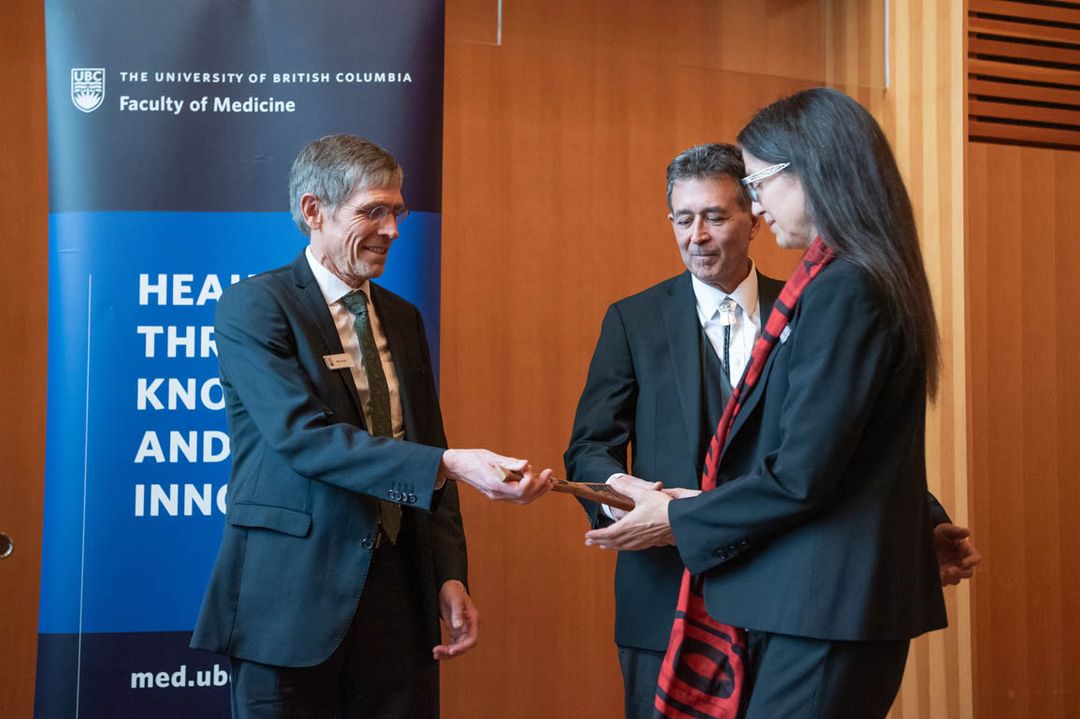

Dr. Nadine Caron being named the founding First Nations Health Authority Chair in Cancer and Wellness at UBC (Credit: FNHA)

What is the most rewarding aspect of your work?

Whether it’s as a physician, surgeon, researcher, or teacher, the most rewarding aspect would be hearing the stories of the people I meet. It’s an amazing honor to be a physician. One of the things you first do when you’re trying to figure out what happened or what could be the diagnosis is to ask questions. You ask questions about where they were and who they are. Then, patients share these amazing personal stories with you. The amount of trust that they put in you to do that never ceases to amaze me. I hope I never lose the gratitude that I have for them to be so giving and so trusting when I’ve just met them.

How would you compare teaching versus practicing medicine?

Anyone in medicine is really teaching it. As a surgeon, let’s say a patient I see has a mass in their thyroid gland. I talk to them, they share their story, and I have my suspicions of what the diagnosis might be. Maybe I ordered some additional tests. Ultimately, let’s say that it comes back, and it’s thyroid cancer. Then, I recommended an operation to them. I have to explain what it means, what the potential risks are, what the potential complications are, what the potential benefits of doing the surgery are, and what their other options are. In the end, you have to get all of this information conveyed so that they can make a choice. Do they want the operation or not? So, even though that patient is not someone that you’re there to teach, you can’t help but be a teacher in terms of explaining all of this so that they can make an informed decision.

"Anyone in medicine is really teaching it.”

Dr. Nadine Caron

I also love the “standard teaching”--teaching medical students, residents, and fellows, who are people that have already graduated from their residency but are doing additional training. I love the standard teaching because it’s very challenging and reminds me of the path I’ve taken; I was once a medical student, resident, and fellow. It also reminds me of the enthusiasm, curiosity, and excitement that I felt at those stages. Third-year medical students, second-year medical students, or first-year surgery residents, they’re excited about things that I sometimes forget are exciting because I do them every day. It’s nice to be reminded that what you do is fun, exciting, inspiring, and challenging. Having the ability to teach students and trainees along that spectrum reminds me of that.

Can you walk us through a typical day in the life?

I don’t think I can walk you through a day in the life. It’s such a diverse career path that I’ve chosen and/or that has been given to me over the years. There are some things that are definitely always consistent. One of the things is being a mom. Checking in and finding out what’s going on in my daughter’s day is one of my favorite parts of the day. But, when it comes to the career, the teaching, or the research, it depends.

Yesterday, I had an OR day. It was an early morning. I got to the hospital, saw my patients, reviewed their radiology images, headed to the OR and talked to the OR team (the nurses and the anesthesiologist), and spent the day in the operating room. In between, I called patients and colleagues and did some work on my laptop before the next case. That night, I worked on a research grant after I got home from taking my daughter out cross-country skiing.

Today, I followed up with my patients that had their operation yesterday. They’re doing great, which is always wonderful to hear. Then, I had some meetings for the Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Health and the First Nations Health Authority Chair in Cancer and Wellness at UBC as well as a lot of research meetings with colleagues, students, and trainees. This afternoon, I have some more clinical work where I’m meeting up with patients and connecting with my office staff.

Dr. Nadine Caron (right) in the operating room (Credit: Ed Ou and Kitra Cahana/CBC)

Tomorrow, I’m going to be pretty busy because next week at UBC, we have a week-long course on COVID in indigenous populations, so I’m really trying to make sure that all of the work is done and ready for the course.

So, you can see it’s a combination of things. No day is the same, and I actually love that. It keeps things interesting, it keeps me on my toes, and it’s a career path that works for me.

How do you find balance in your life?

There are only 24 hours a day and only seven days a week. It doesn’t matter who you are. Everybody’s equal that way. I’m busy. But, I’m working harder and harder on managing that and finding time to get out and do things that I love and enjoy. I think I’ve always done that.

Sports have been an outlet for me. It’s been such a way that I’ve used to deal with stress. Sometimes, I go out for runs on the trails when I need to think. Sometimes, I go for runs in the trails when I want to do anything but think. I can use it both ways. When the snow comes up in northern British Columbia, I cross-country ski. In the summer, my husband and I paddle, which I’ve recently picked up. I love reading, sitting in front of the fireplace with a good coffee.

I love doing just about anything with my daughter, whether it’s sports, hanging out, or just sitting and talking about how she views the world and the things that are happening. I love it, and I certainly can always find time for that.

Dr. Nadine Caron with family (Credit: Janice L. Pasieka)

Can you tell us more about your TEDx talk, The Other Side of “Being First”?

The talk was to hopefully make people think about all those stories that we hear in the media about the “first this” or the “first that” and to ensure that we always take a look and wonder what in that story is the good news. What should we celebrate about the accomplishments of an individual, and what in that story needs to be addressed.

When it comes to massive accomplishments in sports, science, or other fields, sometimes it’s the first because it just takes that many years to do something like that. For example, in the Canadian Space Agency or in track and field. But, in a lot of the news, like in this case when we hear about the first First Nations person to do this or the first indigenous person to do that, we have to stop and wonder, why in 2022 is it the first? Are we covering up faults and gaps and chasms in society when all we focus on is the accomplishment of an individual rather than the pitfalls and the downsides of how society has moved forward as a whole?

“Are we covering up faults and gaps and chasms in society when all we focus on is the accomplishment of an individual rather than the pitfalls and the downsides of how society has moved forward as a whole?”

Dr. Nadine Caron

I’ve really strived to figure out how I can play a role in addressing that. If you’re the first, you’re also the only. I’ve had to recognize that. As the first, you have to figure out how to change the only into a few, the few into the many, and the many into the often. When it comes to STEM and medicine, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done when it comes to representation of indigenous students and communities.

I think the main thing is working at elementary and high school levels and in communities to make learning opportunities available and also fun. They should be encouraging and inspiring for kids, making sure that the messages they get are that these are all doors that are ready for them. All they have to do is open them and step in.

We also have to make sure that the post-secondary institutions are places not only where these students can go but that they want to go. That means creating a welcoming, culturally safe, and supportive environment. When these students graduate, we have to make sure that they have opportunities to get jobs or pursue more advanced degrees.

When an individual sets their goals on what they would love to achieve, whether they succeed or not is really up to them. The systems and the society that they work within are there to support them, not to beat them down or put up barricades. I don’t think we’re there yet, but I think it’s better than it used to be.

Dr. Nadine Caron works closely with UBC’s Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Health, which she started in 2014 (Credit: FNHA)

What do you hope younger students understand about their futures?

My hope is that youth start to realize that their future is really so open and there for them to grasp. I know that they sometimes get messages otherwise. They may hear negative messages, they may hear that things aren’t possible, or they may hear that things aren’t there for them. Those are hard messages to ignore. My theory is it takes 100 positive messages to overcome one negative message.

We need to as a society, as education systems, to really try to shift things so that the students hear those positive messages and feel supported, whether education-wise, support in the systems so they have more opportunity to have the full spectrum of STEM subjects in their high schools to learn, or financial support so when they have dreams and aspirations, they can actually access those and get to post-secondary education institutions.

We need to create a space for these students so that when they’re on social media, when they’re in the classroom, when they’re talking to their parents, when they’re talking to community members, and when they look for role models, they can see enough positive out there to know that they can be part of that story.

Part of it is, too, for those who succeed to turn around and help the youth who see them and want to be like them—to say that they were once in their spot too and they did it, so the person behind them should be able to follow in their footsteps.

What advice do you have for a student who is interested in pursuing medicine?

There’s such a critical role for mentors, someone that students can go to and share their interests, dreams and ideas about what they might do. That mentor can work with the student in their specific situation to help them reach their goal.

When you really want something, be a detective to find out who’s done what you want to do and consider reaching out to them or to the organization they work with. There’s also the role of getting summer jobs in these areas where you’re working in STEM. That’s part of giving back and being a role model. At the same time, you should immerse yourself in environments where people are supportive and who will help you get to your next rung on the ladder of your career pathway.

Dr. Nadine Caron aims to improve cancer outcomes and wellness among Indigenous communities (Credit: FNHA)

What do you hope to see in the future of healthcare?

A big task that we’re undertaking right now in British Columbia and hopefully across Canada is addressing cultural safety in the healthcare system. I think we focus a lot on access to health care, and we don’t focus so much on utilization of health care. Sometimes just because the building exists and there are healthcare providers and resources within that building, if it’s not a culturally safe place to be—if it’s not free of discrimination, negative stereotypes, bias, and racism—it’s going to be a place that individuals do not feel comfortable going to. That’s something that we can and we should and we must address. There’s lots of work that we’re doing on that right now at UBC’s Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Health and in the healthcare profession.

The other thing with respect to the healthcare system is really striving for equity. I call it the elusive chase for equity. As Canadians, it’s a concept that we think that we have. We look at our Canada Health Act and we say that we have this universal healthcare system. But, you don’t have to work too long in the healthcare system to realize that it’s not universal. It’s not fair. It’s not justly distributed. It’s inequitable.

But, I think we can improve that. We have the principles as a country to actually move the healthcare systems that we have province by province, territory by territory, and those specifically for indigenous peoples, into a place that’s equitable, fair, safe, and successful. When an individual walks through the doors of a doctor’s office or hospital, they may be scared of the symptoms or what happened, but in the back of their mind, they know that they’re going to a place that will help. If that’s an underlying feeling of a Canadian, or anybody walking through the doors of a Canadian healthcare institution, I think that would be an amazing accomplishment.