Meet Dr. Julie Mirpuri

Neonatologist

Dr. Julie Mirpuri is a physician-scientist at UT-Southwestern. As a physician, she is a neonatologist, where she takes care of newborn babies either born premature or have other abnormalities in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). As a scientist, she runs her own laboratory, where she conducts research focused on neonatal microbiome development with a goal of developing novel therapies to improve the health of babies.

STEM to the Sky

Nov 16, 2023

- Have you always wanted to go into medicine?

- Why did you choose pediatrics?

- Why did you choose to become a physician-scientist?

- What do you enjoy most about being a physician-scientist?

- Can you describe one of your most exciting research projects right now?

- Was there anything that surprised you when you first began your career?

- What skills would you say are important for being a physician-scientist?

- Can you describe a typical day in your life?

- What advice would you give to a student interested in pursuing medicine or STEM in general?

Have you always wanted to go into medicine?

I’ve always loved medicine. I’ve actually always wanted to become a doctor. I have an older brother who has special needs, so my mom had to take him to many doctor appointments when he was growing up. She would come home and make a lot of comments about different kinds of doctors, and I remember her sometimes crying and feeling like there was no hope. But, there was one particular doctor that my mom would come home from seeing and say, ‘She is such an amazing doctor.’ She would give her confidence and positivity. One day, when I was around six years old, my mom said, ‘You must meet this doctor.’ So she took me and my brother with her to go see this doctor. I saw this physician who had a fantastic bedside manner and the ability to make my mom feel reassured through her communication skills. I could see from my mom how much hope she gave. That was one of my first real experiences in healthcare and medicine, and I thought, ‘This feels good. This feels right. This is who I want to be.’

"That was one of my first real experiences in healthcare and medicine, and I thought, ‘This feels good. This feels right. This is who I want to be."

Dr. Julie Mirpuri

Why did you choose pediatrics?

When you decide to become a doctor, there are so many choices: dermatology, radiation oncology, hematology oncology, cancer research, obstetrics and gynecology, etc. During medical school, you get a taste of everything.

When I got a taste of pediatrics, I just fell in love with it. I love kids. To be honest, one of the things is that adults sometimes don't listen to you when you give them advice, but kids do. We give them their medication and there's no complaint per se. I feel like with adults, that was my struggle. When I was in medical school, I would say, ‘Exercise more, take your medications’ and on the next visit, they would say ‘I didn't take my medications’. That was one of the biggest things that attracted me to pediatrics. I love kids, and I felt like I could make more of a difference.

The first time I went inside a NICU, (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), I was just in shock. I walk in, and I see all of these incubators with tiny little human beings inside—some of them don't even look like complete human beings because they’re so small. The first baby I saw in an incubator was 500 grams, and I thought, ‘Wow, this baby can survive, it wants to survive.’ The neonatologists are doing their best to try and make this baby grow, and a lot of them do grow well enough to go home. I thought, ‘Wow, this is such a satisfying field. This is what I want to do. This is the population of babies and kids that I want to take care of.’

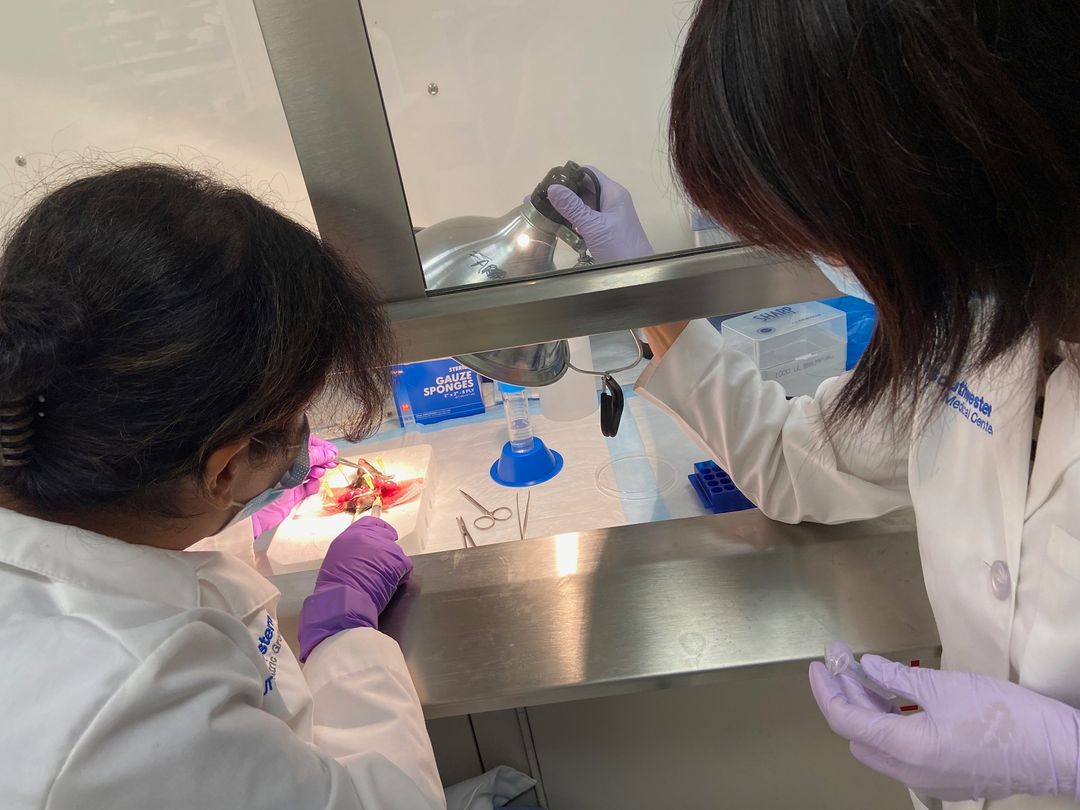

(Credit: Dr. Julie Mirpuri)

"The first baby I saw in an incubator was 500 grams, and I thought, ‘Wow, this baby can survive, it wants to survive."

Dr. Julie Mirpuri

Why did you choose to become a physician-scientist?

I grew up in Hong Kong and went to medical school there. I had no idea I could be a doctor and a scientist with my own lab until very late in my career. When you become a neonatologist, you have a period of time of training called fellowship, where you get time protected to do research. During that time, they said ‘Why don't you join a basic science lab?’ I said, ‘Well, I've never done it before.’ They said to try it, so I did, and I just loved it. The idea of being able to come back from the hospital, think of ideas, and be able to test them or to come up with new potential ways to treat the babies was really exciting for me. Though I didn't know I was going to be a scientist, I fell in love with it later in my career as I invested more time. I think I’m a good example of somebody who didn't follow the advice that some people gave me about what I would be best at, and instead, stuck to what I loved.

What do you enjoy most about being a physician-scientist?

Right now, one of the most wonderful things about my job is getting to teach. When you're a physician-scientist, you’re always in a university environment, so I get exposed to a lot of college students, medical students, residents, and fellows. Some of them join my lab, so I had a fellow recently who won a couple of big prizes with the research he did with me. I also have a high school student who comes every year for the summer, and she's applying to medical school now. I mean I love the science. I love taking care of babies, especially when they get to go home. I love when the parents are so thankful, and I love making discoveries. But, the thing I’m most satisfied with is being able to pay it forward and see young people be successful as they pursue their careers. That really brings so much joy.

(Credit: Dr. Julie Mirpuri)

Can you describe one of your most exciting research projects right now?

One of the biggest things I'm working on right now is understanding how what mothers eat during pregnancy can affect the baby's health in the womb. For a long time, people didn't really think about that. They thought that as long as mothers eat enough, the baby will be healthy. In our lab, however, we are trying to understand the effect of a specific diet on the baby’s health, especially high-fat diets because we have an obesity epidemic around the world, especially in developing countries. We are studying in mice how having a diet that is very high in fats/carbohydrates for the mother can affect the baby.

We found that the type of food the mother eats gets affected by the bacteria that she has. This produces small substances called metabolites, which are present in the amniotic fluid that the baby is covered with. The baby is constantly swallowing this fluid, so these little metabolites are affecting the immune cells in the baby’s intestines even before birth. Now, we believe that what mothers eat when they're pregnant is preparing the baby for what they're going to be exposed to. If they eat a bad diet, that baby's immune system is primed for that. Babies who are born to mothers or parents who are obese or overweight are more likely to become obese and overweight as well. These babies are also more likely to have heart disease, hypertension, and all of these other diseases.

I'm very excited because we're starting to find a signal that could be important even at the time of the womb that we can potentially change. Now, I always tell young people who are pre-pregnancy that, ‘People always tell pregnant women, you're eating for two so you can eat whatever you want, but that's not true. Eat well, eat carefully, and eat the right vegetables because your baby inside you is using that as an example for the rest of their life.’ We hope to develop some of these small molecules into supplements that pregnant women can take, so that once the baby is born, they have been exposed to good metabolites that can help them have a healthier life in the future.

Was there anything that surprised you when you first began your career?

When I was doing my pediatric training, I was really surprised by how smart adolescents are. Adolescent medicine was one of my most fun rotations because, of course, I went through it, but when you look at it from a physician's perspective, it's different. It's such a challenging, exciting time at that age when you are 13 to 18. You are in that mid-phase between still being a child, and then transitioning into adulthood—it’s so hard. It brought back some memories, but it also made me think that adolescence is a very resilient and challenging time. It really gave me a lot more respect for that period of time. That surprised me a little bit because I thought that I had understood what being an adolescent was, but it's only when you go through the spectrum and meet so many different people from so many different backgrounds that you start to see some of the health conditions that they're going through.

Even right now, it's such a different world than when I grew up. When I was an adolescent, the internet was just starting. We didn't have Facebook or Instagram. You just compared yourself to the people who are around you and other schools. Now, it's as though the whole world is comparing you to everyone else. It was already a hard time when I was going through it, but I think now, it’s an even harder time. That surprised me and challenged me to think more about it because it’s such an evolving exposure during that time. In pediatrics, though it is not my particular field, we need more people who are doing adolescent medicine because especially at that particular time, with all the stresses, that’s when adolescents need the most support.

(Credit: Dr. Julie Mirpuri)

What skills would you say are important for being a physician-scientist?

I do a lot of chemistry, ironically. When I was studying chemistry, I didn’t know when I was going to use it. Even through medical school I didn't use it that much. Then, when I went back to research, I now use chemistry all the time. We are calculating molar fluid, doing western blots, etc. Biology, of course, is also very important. I think math skills are still very important as well, especially in these little babies where we have to do such intricate calculations. We have to calculate how much glucose we are giving them, how much fat (in relation to their weight), additives, and dilution.

You also have to use your hands a fair amount. A lot of these babies are born without being able to breathe, so you have to put a tube in to help them breathe with a ventilator. Babies are born with access to their veins and arteries because they're born with the umbilical cord, so you have to put lines in there to give them nutrition until they can eat.

Being able to communicate in a team is very important. Especially in an academic hospital setting, medicine is a team sport. I work with a lot of great people, including nurse practitioners, nurses, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, medical students, trainees, residents, and fellows. Being able to work in a team and being able to teach something are both very important. We have a saying in medicine: see one, do one, teach one. If you’re trying to learn something, you see somebody do it first, then you do it, and to become a real master, you teach it. You can do that as early as you want, even when you're in school.

The right mindset is important too. Don’t be so hard on yourself. You're going to fail sometimes. I failed some exams—it's just going to happen. There are many times when you don't know the answers, but you can always do better and you can always improve. It's a learning process throughout your life. If I don’t get a grant that I submitted, it's not a failure of me as a human being or that I'm not good enough. It's that process of reflecting and submitting it again. Then eventually you do get it. Having that mindset of ‘I can do this. I am capable. One small failure is not a failure of me.’ is one of the many skills you need to really be successful, particularly in these long careers where you have to train for a long period of time.

Can you describe a typical day in your life?

I wake up really early in the morning and head to Orangetheory. I used to try and go to the gym, but I was never motivated, so I go to this group workout. You don’t have to think—the instructors tell you what to do, and they play good music. Then, I go home and spend some time with my kids, get ready for work, drop them off at their school, and come into work. My day from there depends if I'm working in the hospital or if I'm only doing my research.

I spend about 10 to 12 weeks just in the hospital, taking care of those babies every day along with my teaching. When I'm in my hospital blocks, I go straight to the hospital where we have a meeting with all the teams to talk about the babies that we're expecting and the sickest babies. We meet with the radiologist to go through X-rays of all the babies that we need to look at. Then, we start what we called “rounds”, where we walk around the bedside of each baby. We talk about the plan for each baby, and we put in orders. After that, I examine all of the babies and talk to the parents. If there are any new babies that come in, we go see them. If there are babies that are being delivered, I go attend those deliveries with the trainees. I love that part because you get these fresh new babies, and you help them survive. In the afternoons, I teach the residents and medical students and finish up notes. At around 4 PM, I sign out to the incoming team who comes in at night and tell them about the babies I’m taking care of. Or, if I'm on-call that night, I stay the night and leave the next day. Then, I go home to my family, eat dinner, and spend some time on my research.

On the days that I do research, I do the same thing in the morning, but I go to my laboratory where we plan experiments for the day and talk about our goals for the week. There are some days where I actually do experiments and other days where I’m analyzing data or reading articles on specific research I’m doing. I may also be writing papers and grants, which is a way to get funding for the research that we do. It’s very varied, which I like because my days don't always look the same. When I’m doing research, there is some work-life harmony that gives me more flexibility. For example, if my kids need me for an event at school, I can leave earlier to pick them up and spend time with them.

(Credit: Dr. Julie Mirpuri)

What advice would you give to a student interested in pursuing medicine or STEM in general?

First, don't listen to people who are saying negative things. Everybody that I know who is a successful scientist, physician, researcher—anybody in the STEM field—will tell you about some people along the way who have said, ‘Don't do that. You won't be good at it. You should think about this.’ The same thing happened to me. Instead, do what you love and really follow your passion because that will make it worth it. I may have been a fantastic lawyer, and I might have been really good at it, but I don't think I would have woken up in the morning and felt like this is what I want to do. Passion is what makes you wake up in the morning and want to go to work. I really believe that the key to success is loving what you do.

The other thing would be to have that mindset to recognize that your value is always there. Even if you don't get that prize or scholarship, there are other things you will get and it doesn't change your value. Stay positive. The biggest thing you can do to stay positive is to surround yourself with positive people. Recognize the energies around you. There are people who are negative and bring you down, but there are also people who say ‘You can do this. I’m so proud of you. Let’s do this together.’ Hold on to those people because they will help lift you up.

Learn More:

- IF/THEN: https://ifthenexhibit.org/ambassador/T-14/

- Dr. Julie Mirpuri: https://utswmed.org/doctors/julie-mirpuri-hathiramani/