Meet Camilo Rebelo

Architect

Camilo Rebelo is an award-winning architect. After completing his studies at the Porto School of Architecture in Portugal, Rebelo went on to teach at many institutions worldwide. His hundreds of projects explore the connected relationship between urban architecture and protected natural landscapes.

STEM to the Sky

Jun 5, 2022

- Have you always wanted to go into architecture?

- What surprised you most about architecture?

- Can you walk us through the design process for your projects?

- What is your favorite project that you have worked on?

- Where do you draw inspiration from for new project designs?

- How would you compare teaching architecture to practicing architecture?

- Can you describe a typical day in your life?

- What advice would you give to a student interested in architecture?

- What do you hope to see in the future of architecture?

Have you always wanted to go into architecture?

Since I was a kid, I’ve always liked to do drawings and compositions. There was also another field of research, which I loved: biology. From animals to plants, I was always very interested in everything that concerns biology and geography. When I was 12 or 13, I started to become oriented toward the arts. I loved to see spaces and historical buildings.

I was in a German high school in Portugal that I loved. But in the last two years, it was not so much oriented to architecture. So, for the last two years, I moved to a Portuguese high school where I learned the first approaches to architecture and the great masters of architecture.

(Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

What surprised you most about architecture?

When I was 18 years old, I was at The Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto (FAUP). The methodology of the school, which still is today, is to draw. The obsession with drawings in all of these dimensions from color, composition, and simple sketches, was a new universe. This ability to relate the drawings to the construction of ideas is critical. In high school, you develop drawing as a tool and a way to express yourself. But when it came to using the drawing and exploring the dimensions, that enlightenment came from the university. Architecture is two-fold. It’s a technical skill because you utilize the skill of drawing, but it’s also a mental skill. Both, you develop at the same time. A sketchbook is very important as it is registering and capturing your thoughts at the same time. One hand brings information to the brain, and the brain brings the information back to the drawing hand.

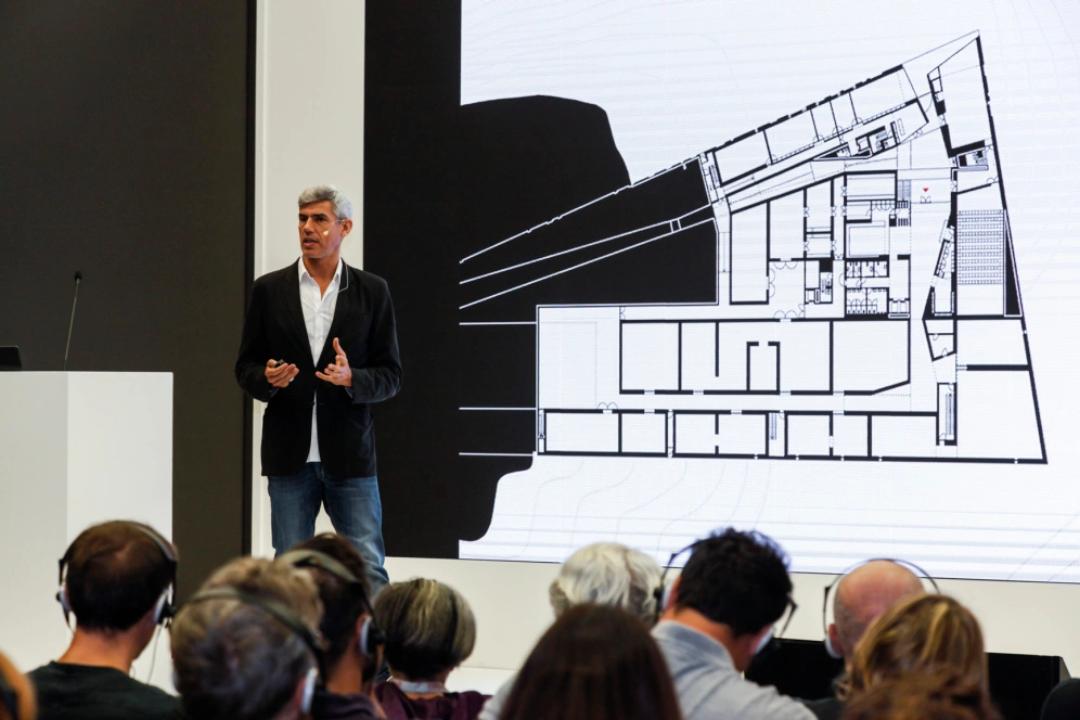

Can you walk us through the design process for your projects?

From the first day I opened the office, I have not been a copy-paster. We are driven by creating. The second thing is always to create something that contributes to architecture. An architect has to be a positive person, individually and collectively. The office has a team of engineers and a team of landscapers. As architects, we need people who are positive and constructive. When it comes to architecture, your effort is always 110%. If someone on the team becomes full of doubts and weakens up the process, it becomes a shaky project.

The Côa Museum

The Côa Museum was created for a competition that we won. The jury gave us the first prize as they considered it an outstanding approach to relating architecture and nature. With this project, I was able to go back to my beginnings and my passion for biology. The Côa Valley Project is a double-protected site in heritage because of the landscape and the Paleolithic art engravings. There was a big responsibility in this project because if you are doing a museum that’s going to be the landmark for a region that is protected in heritage, it means that you have to make a serious compromise. When we excavated the hole to start the build, we took half of the mountain away. To build that 200-meter-long concrete piece, we had high demands and considerations. You can only imagine the number of doubts we had and the number of problems that we had to solve to make a piece that is considered by the jury as highly intriguing.

The Côa Museum (Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

The Ktima House

The Ktima house is located on an island in the Greek archipelago. The clients wanted a very big villa for a vacation home. We realized that we had two problems. First, we were building in a valley, which is very difficult because you also want to have a view of the ocean. Secondly, they wanted the home to be hidden in the valley, yet they wanted something very big. If you make the home a straight line in the valley, it would be a 200-meter long bridge. How can you integrate a 200-meter-long villa facing the ocean if you want to make it part of the valley? If you imagine a 200-meter-long train, what we did was we cracked the wagons: there were no more straight lines. There is also a regulation in Greece that says that the segments should not be longer than 10 meters. We adapted each of the 10-meter segments of the villa and placed them in the valley. It became like an amphitheater.

The Ktima House (Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

What is your favorite project that you have worked on?

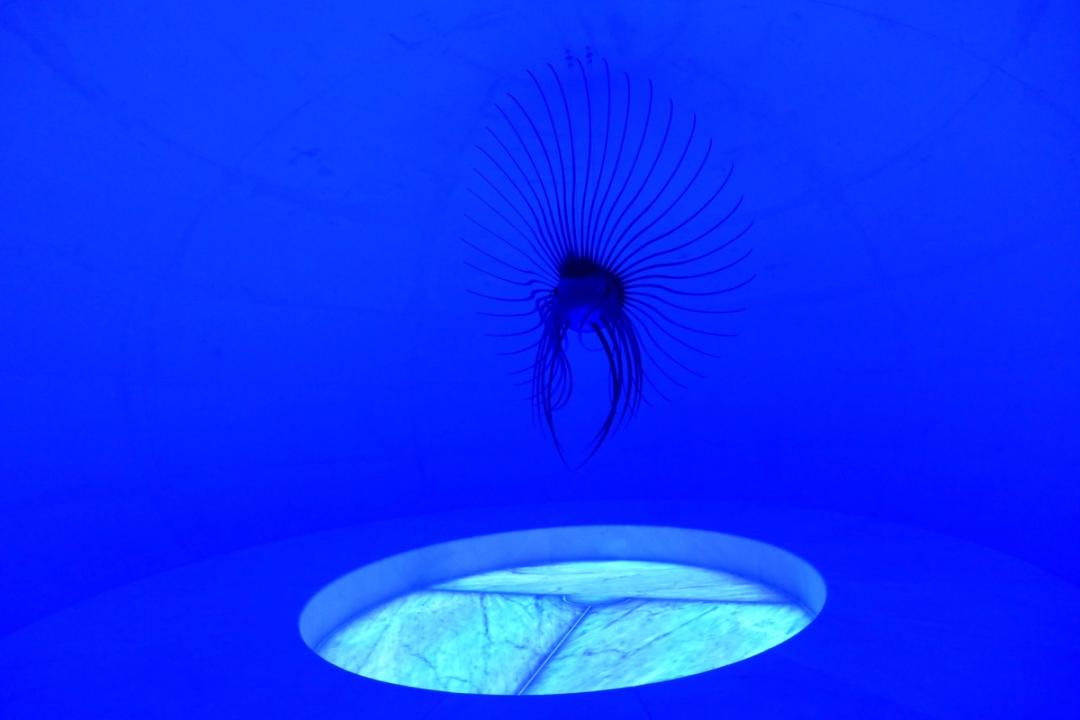

We did a very nice small project that’s 21 square meters in the mountains of Switzerland. It’s called Egg or Ovo. It’s an exhibition room, but most of it is used as a meditation room for your “rebirth”. You go there, breathe in and breathe out, and come out a different person.

Ovo (Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

We have a number of other projects that I’m very happy about, from producing the Portwine Museum in the city of Porto to a house we are doing in the South. This house is magical because it has a double shelf. The exterior shelf has an air cushion in between the wall, so when it’s cold outside, the cold air doesn’t go inside and vice versa. The air cushion in the middle balances the continuous temperature of the inside without any air conditioning or heating system.

We have many projects that we are very proud to have been a part of, but we are always open for the next one. I’m very passionate about past projects, but I’m always driven by what we can do next. We don’t live in the past: we learn from the past and use our knowledge from the past to serve the future and the new demands.

Portwine Museum

Promise

(Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

Where do you draw inspiration from for new project designs?

I use an expression that, sometimes in architecture, is not very welcomed. I feel like I’m here and I’m spiritually bound with the planet and the universe. On the other hand, I’m a very intuitive person. The third thing relates to my subconsciousness. Our brains have very little consciousness: about 3% to 6%. A person who is considered creative is actually only utilizing 3% of their capability. What I have been doing for 15 years or more are therapies to unblock and release my subconsciousness. The less blockage there is in your mindset, the more possibilities there are for you to relate unprobable things. You always have to combine at least what is known with some unknown. If both are unknown, that’s also good, but that’s more difficult to control. So far, I am happy with the known and unknown.

“The less blockage there is in your mindset, the more possibilities there are for you to relate unprobable things.“

Camilo Rebelo

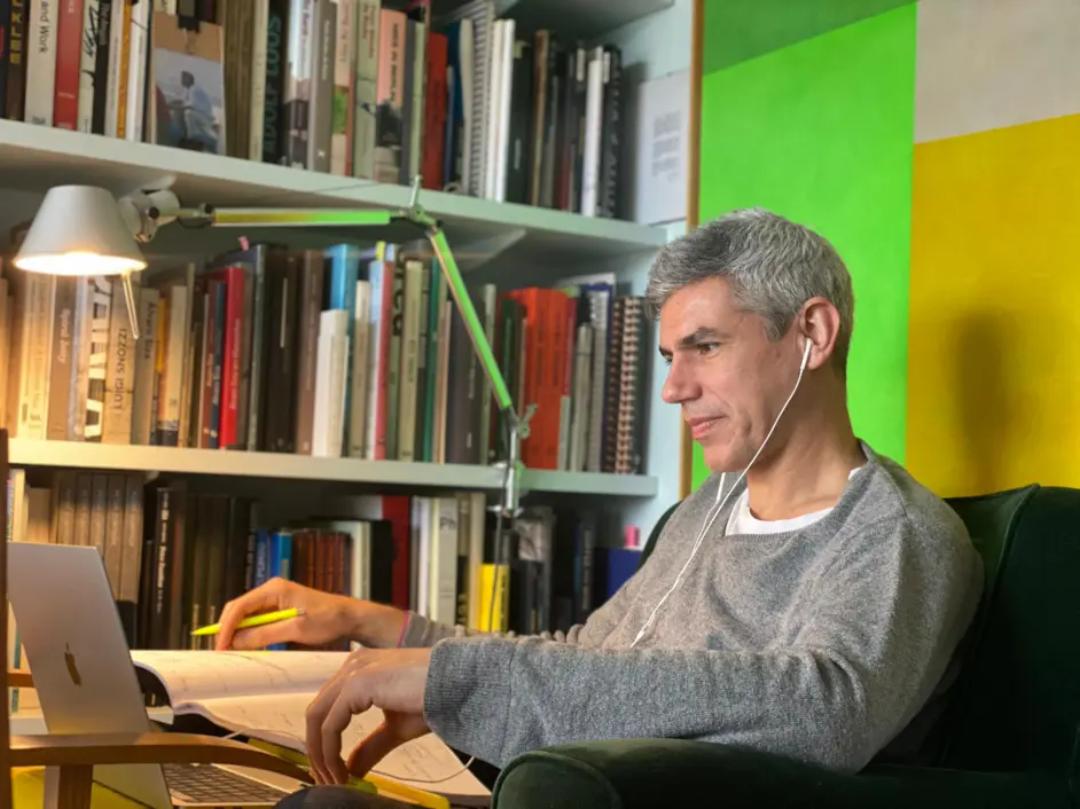

How would you compare teaching architecture to practicing architecture?

In the Classroom

I started to teach when I was 27 years old, and I’ve had the opportunity to teach in many different countries. I taught at Porto University in Porto, Portugal for almost 14 years; Lausanne, Switzerland for five years, Pamplona, Spain; Shanghai, China; and Italy for the past seven years.

Mostly what I bring to my students are my office concerns because I think they already have steady academia. One of my favorite books is Steve Jobs’ biography. Jobs went to university but remained more of a freelancer in academia. In academia, there are fantastic things to do with knowledge and logic that are systemized and well-processed, which is important in the formation of a student. But also, you have to connect your studies to the world and to the constant current around you. Sometimes, universities don’t have the capacity, flexibility, or speed to adapt to reality. If you bring your concerns from the office or from your world perception and then plug in academia, then you are very balanced. I think the students love that. Again, it’s what you know and what you don’t know.

(Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

In the Office

I always see the advantage of collaboration. Of course, there is Camilo Rebelo, but I’m never by myself as an architect. I come along with many associates and partners. From engineers to architects, I always need the spirit to team up and partner with others. Otherwise, I think I would stand still, and I’m not interested in standing still. Like photographer Robert Frank once told me, I have to keep moving. You have to always have this drive to keep moving forward and see what’s coming next.

(Credit: Camilo Rebelo)

Can you describe a typical day in your life?

This depends very much on the season we are in and if I’m teaching abroad or not. If I’m not teaching, I really love to work at night. Maybe this feels a bit anxious about the future, but my first hours of the day are normally between eleven and one or two o’clock from the day before. Mornings are not my thing because I worked the night before. Normally, I go and stay in the office for the rest of the morning and afternoon. The days are quite simple in a way. It’s just the excitement of sketching and drawing in the office and checking models. We work with a lot of models and renderings.

I started my semester in Milano now, so a typical day would be me waking up at four o’clock in the morning and taking the first plane at six. I would be in Milan by nine, teaching in the late morning. Then, I would be teaching all afternoon, staying one night again. The next day, I would be at the studio discussing with all the students and then flying back home. There is no typical day, and I think that this is the exciting part of being an architect.

There is a very steady part in the architecture and also a very unpredictable part. Going back to the duality, life has to do with steadiness and openness.

What advice would you give to a student interested in architecture?

I will give advice that was taught to me by two masters. The first master was Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, who I met when he was 99 years old. He taught me that if you want to be a great architect in the sense that you are open to the world of vision and producing a new step for architecture, you have to be a universal thinker. You have to be engaged with everything. You have to be able to go out for dinner, for a party, to go to the beach, to eat, to drink, and to see exhibitions. You have to be both steady and playful. It’s very important to stay focused in your discipline, but our discipline needs the world. So, you have to be very open to many different realities, cultures, and trips.

The second advice was given to me by Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza, who won the Pritzker Prize in Portugal. He taught me that time is the best architect. If you want to be a great architect, you have to be able to let the projects go. Architecture needs time. The architect needs time: time to grow and time to find the right process. We cannot always be in a hurry. Of course, we hurry a lot. Many times we have schedules to deliver and deadlines. But the perception of time is quite open, it’s like expanding the present. If you always live in the past, it’s wrong. If you always live in the future, it’s also wrong. Architects have to stretch the present and make the present bigger. In that sense, time is very important.

Of course, I have received so much other advice throughout my life. Don’t be too conservative because otherwise you are always being a classic in the approach of architecture. Think about abstraction and figuratives. I love all the recommendations I’ve been given from so many different people, but these two pieces of advice—you cannot be a specialist in architecture and time should be one of your best friends—are definitely the ones that I would forward to future generations.

What do you hope to see in the future of architecture?

In the future, I hope to see steady and long-lasting architecture. The world cannot chop down trees and tear down mountains for provisory architecture. We cannot handle it anymore. We are going to ruin all of the world. Everything has to be done in very precise and careful actions.

On the other hand, I think that architecture should be very efficient when it comes to energy. We have to find ways that our architecture lives within each context and extracts from its reality. If we are in the desert, we should not build a glasshouse. It’s not efficient. Of course you can say, ‘Oh, we can put 100 solar panels around the glasshouse and now it’s clean,’ but what is the purpose of building and extracting materials for 100 solar panels to drop down the temperature within a glass cube in the desert?

“We have to find ways that our architecture lives within each context and extracts from its reality.”

Camilo Rebelo

Learn More:

- Camilo Rebelo's Website

- OLIM Book

- World’s Most Extraordinary Homes: BBC, Netflix